When a famous jazz-rock band and a Coal Region disco owner clashed over the Three Mile Island nuclear meltdown

In May 1980, one year after the meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Middletown Pennsylvania, the famous jazz-rock band Blood Sweat, and Tears released its final album, “Nuclear Blues”. Its title song, written by lead singer and anti-nuke activist David Clayton Thomas, was an angst-written ballad about the Three Mile Island nuclear meltdown just over a year earlier. In that year between the meltdown and the album’s release, my dad and David Clayton-Thomas were engaged in a steel-cage grudge match over whether the band would play a concert at my dad’s discotheque “Movements” in the Eastern Pennsylvania coal town of Mt. Carmel, less than one hour from Three Mile Island. This story charts how Coal-Region ambition, celebrity activism, and an environmental crises created a David and Goliath battle at the end of the disco-age.

EPISODE 2: “THE DISASTER” (links to Episodes 1 and 3 are at bottom of this post)

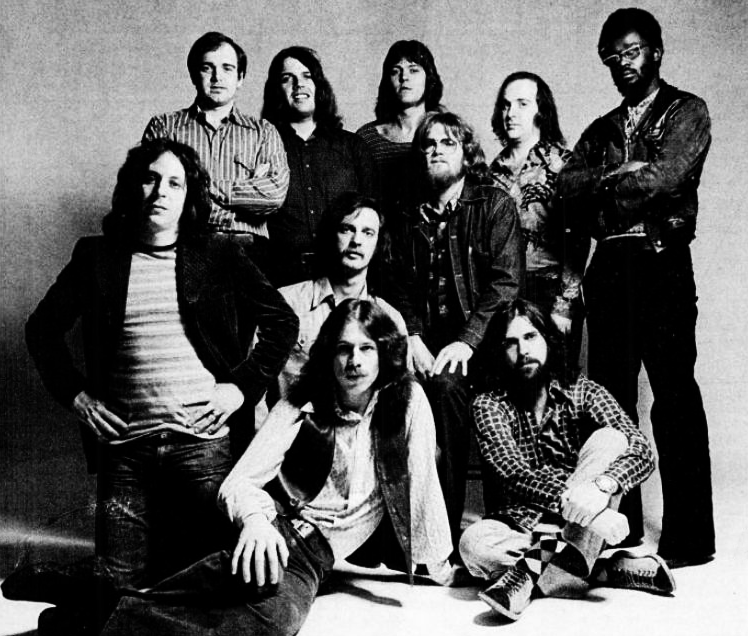

David Clayton-Thomas grew up in Toronto and cut his teeth in the early 1960’s playing rock, jazz, and blues in the Young Street strip. In 1967 he joined Blood, Sweat, and Tears, which already had released one album, and supercharged their group as the lead singer. In 1968 the band soared to international fame with their namesake album “Blood, Sweat and Tears” which sold 10 million copies, topped the Billboard album charts for 7 weeks, won five Grammy’s, and contained the hit singles “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy”, “Spinning Wheel”, and “And When I Die”.

By the time my dad drove to New York a decade later to book a major band for Movements, Clayton-Thomas had left the band, cut several solo albums, and then rejoined the group in the mid-70’s to make a few more albums with a new set of Blood, Sweat, and Tears band members. They were well past their hey-day but still had international name recognition and played a circuit of festivals, casino-show rooms, and clubs.

You couldn’t quite blame my dad for wanting to book a “sure thing” when he set out through the Coal Region along Route 61 toward the Big Apple, three hours due east. Movements had seen local and regional bands on Saturday nights (as a kid I remember my dad admonishing a lead singer for throwing the f-bomb in front of me during an afternoon rehearsal). But my dad was resolved to sign a well-known group in order to garner media attention, lots of out of town guests, and to catapult Movements to become the Studio 54 of Eastern Pennsylvania.

You also couldn’t blame him for declining the booking agent’s offer to sign a then-unknown group, which had just formed in 1978, at a bargain-basement price. Dad passed on the band Toto, who a year later would release one of their first hits, “99”, which rose to number 26 on the Billboard charts, and helped launch the band into stardom with later songs like “Africa” and “Rosanna”.

But with $10,000 in his pocket, which gave him only one shot to take Movements and the town to the bigtime, dad made the wise choice. Few knew Toto yet, but everyone had heard of “Blood, Sweat, and Tears”. They were a sure thing: a risk, but a calculated risk. He signed the contract and drove back to Mt. Carmel every inch a hero. Word spread fast, and ticket sales outstripped Movements’ capacity. The concert had to be moved to a larger venue: the Mt. Carmel High School gym. This event would be a Big F’n Deal for the area.

And then disaster struck.

On March 27th, 1979, during a routine attempt by operators to unclog a common blockage of resin in the secondary cooling system of Three Mile Island (TMI) Nuclear Generating Station, a small amount of water was pushed into an instrument airline past a stuck-open valve, tripping the steam generator system and causing an emergency shutdown of Reactor II. The three auxiliary coolant pumps that would normally get triggered to cool the reactor during such an incident had been shut down that week for routine maintenance, a violation of Nuclear Regulatory Commission rules, so no water was pumped in. This led to a series of human and mechanical errors which eventually caused a partial meltdown of TMI Reactor II’s core and the eventual release of radioactive gas and iodine into the environment. The worst nuclear accident in U.S. history, the TMI meltdown led to the voluntary evacuation of over 100,000 residents of the nearby Harrisburg PA Metro-area.

The evacuations didn’t extend as far as Mt. Carmel, and at no time did the radiation released reach dangerous levels, according to experts. So to my dad, the meltdown by David Clayton-Thomas was just as devastating as the TMI meltdown. The singer informed him, in no uncertain terms, that Blood, Sweat, and Tears was not coming anywhere near f-ing TMI. Clayton-Thomas had been an anti-war activist during the Vietnam era and was an anti-nuke activist now. Big political battles had swirled around the construction of nuclear power plants in the 70’s like another one near Berwick also less than an hour away. By refusing to play the concert he was taking a stand.

On one hand you could understand Clayton-Thomas’ point: There was a disaster in an industry he opposed, and why come anywhere near this small town disco to, in his mind, risk his life. The lyrics in “Nuclear Blues”, released the next year, give you a glimpse into Clayton-Thomas’ state of mind regarding TMI:

“What you think this world is coming to

What you think the man is going to do?

I got nothing I can do about it Paranoia

Nuclear Blues”

On the other hand, who was he standing WITH? The people of Mt. Carmel and the Coal Region LIVED there, they were being told they were safe and not to evacuate, Governor Thornburg stayed in Harrisburg the whole time, and President Carter had toured TMI itself after the meltdown. Most of Mt. Carmel, which was a working-class town, didn’t have the luxury to leave. By the late 70’s most of the area’s major mines had shut down, and the economy had long since collapsed. To us, it felt like we were the ones being abandoned.

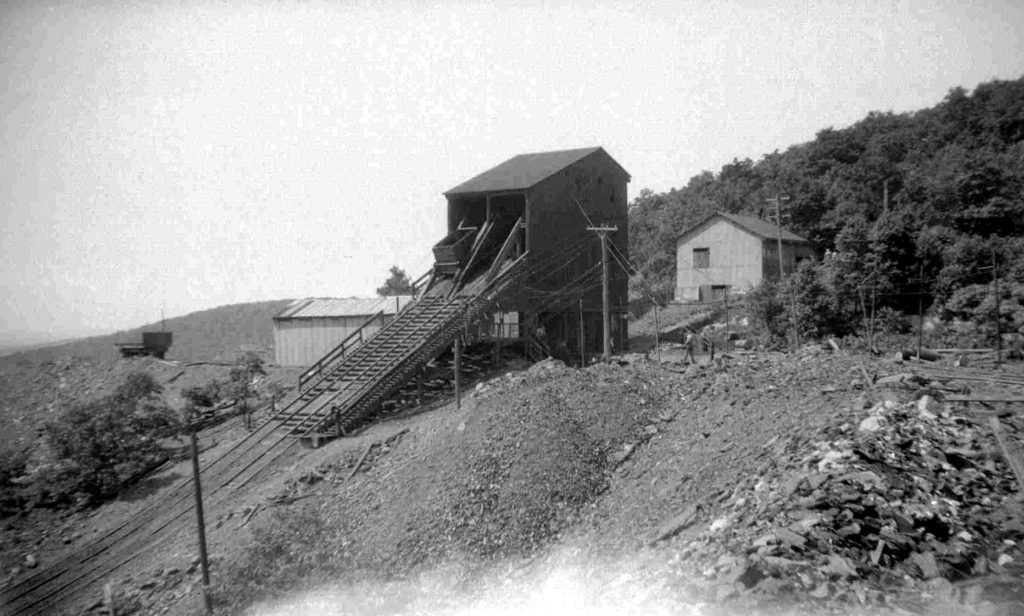

Coal Breaker near Mt. Carmel

New Strip Mine near Mt. Carmel today

This was the biggest event to happen to the town, outside of football, in a long time. After all, if BST played in Mt. Carmel, what other bands might come in the future? What could this mean for Movements? For this part of the Coal Region?

If the experts were saying life must go on uninterrupted for the people of Mt. Carmel, so my dad said the show must go on for Blood, Sweat, and Tears. Sure my dad’s own personal ambitions were mixed into this, but he was a businessman, and he had a signed contract from his New York trip to book a band, and he told David Clayton-Thomas that he would hold him to it.

Stay tuned for “Episode 3 of Disco Inferno: I Will Survive”

CLICK HERE FOR “EPISODE 1 OF DISCO INFERNO: MT. CARMEL IN THE DISCO AGE”

2 Replies to ““DISCO INFERNO- Episode 2: The Disaster – by Doug Greco”

Comments are closed.