(Special thanks to my mom, Candace Greco, for supplying many of the stories and pictures for this piece on my grandmother, Annabelle Costello)

PROLOGUE

During Parents’ Weekend at Brown University, students traditionally took their families to see the famous Newport Mansions, wealthy Gilded Age estates just a 40 minute drive south of the Providence, Rhode Island campus. A wealthy seaside city at the tip of Aquidneck Island, Newport had once been “America’s Society Capitol”, where the Industrialists of the late 1800’s built opulent summer resorts with their untold fortunes: The Astors and Belmonts of the New York financial world, Philadelphia Coal Baron Julius Berwind, the Duke tobacco family of North Carolina, and of course the Vanderbilts, the “First Family” of Newport, who built several historic mansions in including the granddaddy of them all, “The Breakers.”

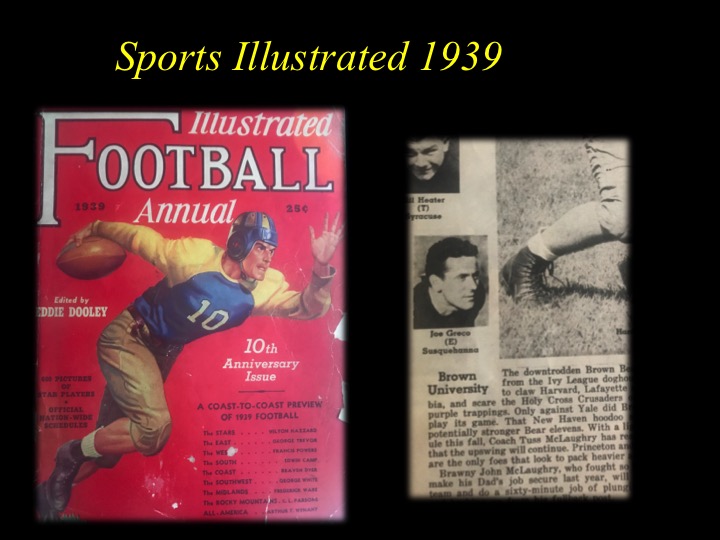

When Nana Costello, my maternal grandmother, made the 6 ½ hour trek to Brown with my mom and younger brother to parents weekend from Mt. Carmel during my freshman year in 1990, I wanted to show off the Newport mansions. Proud of making it to an Ivy League school, where I played Freshman football and majored in Economics, I wanted to show my family a part of New England much different from the Coal Region of Pennsylvania we hailed from. With guidebook in hand, I drove them past each estate, narrating the tour with bits and pieces about the lives of the different Robber Barons responsible for building each. But something strange was happening with my grandmother. .

Nana, though short and slight in stature, normally held court in every conversation. But now she was unusually silent. In fact she didn’t say a word during the entire tour. No awe-inspired gasps, no historical commentary, which as an avid buff of history and politics she loved to supply. Normally she would have been a spark plug in the conversation. But today: nothing. During the only guided tour we took inside one of the mansions, she decided to wait in the car. With a grim face, she totally tuned out.

Nonetheless, at the end of the day we made one final stop at The Breakers, the signature mansion of Newport and epitome of Gilded Age decadence. Built by Cornelius Vanderbilt II in 1895, The Breakers breathtaking size and stately beauty is drawn in sharp relief against an impeccably manicured, football-field sized front lawn which faced the brackish Easton Bay. The famous Newport Cliff Walk ran the course of the water’s edge, overlooking the crashing ocean down below the lineup of mansions. We took the winding driveway to the edge of the Cliff Walk to capture the iconic ocean view of The Breakers.

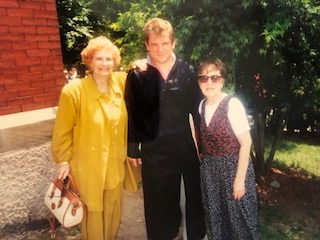

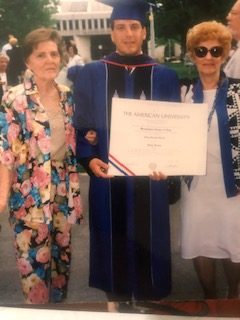

Nana Greco (left) and Nana Costello (Right) at my college graduation from Brown

The gardens at The Breakers

My mom, my brother and I jumped out of the car and walked towards the viewing area at the edge of the lawn, when I turned back to Nana:

“Why don’t you just come out of the car and see this one?”

“No, I’m ok,” she said curtly.

After seeing the disappointment on my face, she relented.

“Ok, One. Just this one,” she said.

We walked to the chest-height stone wall where my mom and brother were gazing at The Breakers’ splendor. Nana looked at the estate for barely a few seconds, and declared:

“Ok let’s go,” and turned back to the car. We followed.

Once inside, I aired my frustration.

“What’s wrong? You’ve been silent all day. You’ve been grouchy. You wouldn’t go on the tour or get out of the car. Why get out now? If you weren’t going to enjoy it, why bother?” I was irritated.

She took a long pause, then answered, barely holding back her rage. With two fierce and cutting sentences, she put me in my place:

“Your grandfather worked in those coal mines his whole entire life, and died a poor man. I just wanted to see where all that money went.”

No other Economics lesson in my four years at Brown stuck with me like that one.

GROWING UP

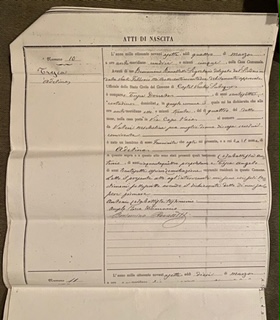

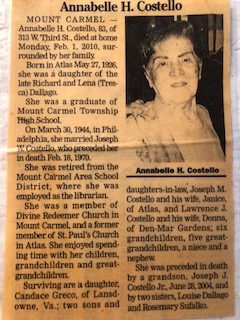

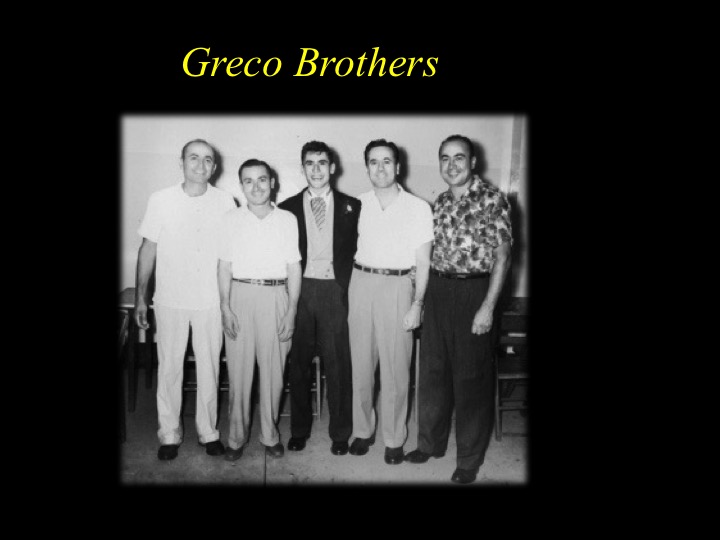

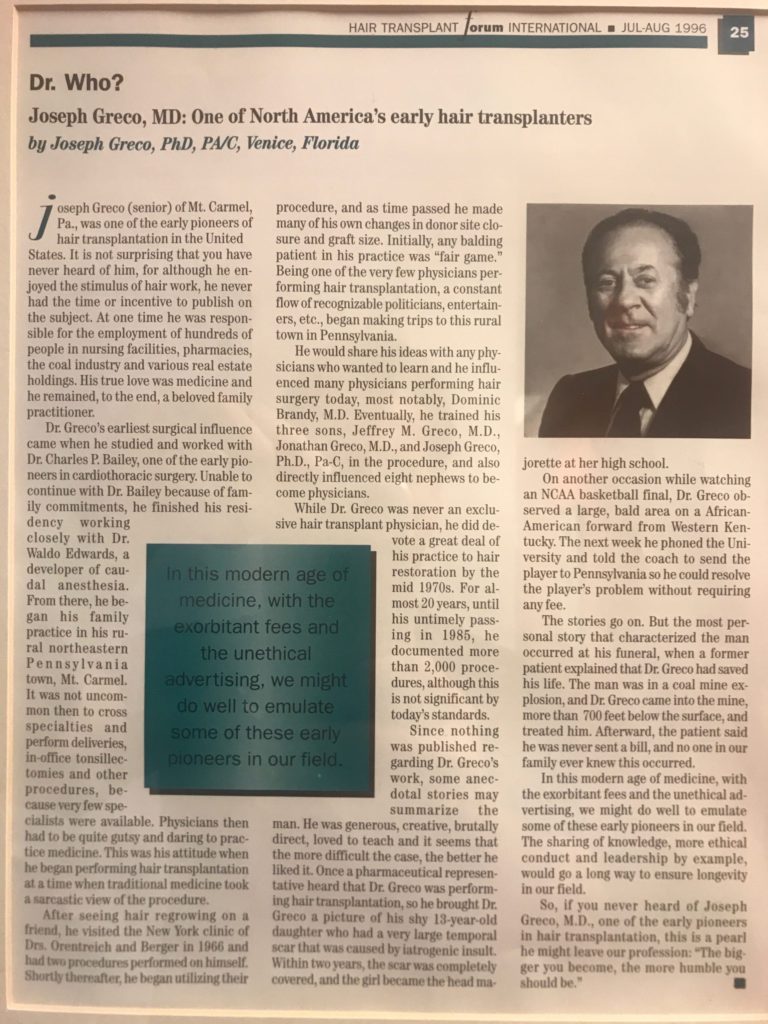

Richard and Lena Dellago, both immigrants from the poor Abruzzo region of Central Italy, raised their two daughters, Rosemary and Annabelle, on Girard Street in Atlas, Pennsylvania. Formerly known as “Exchange” for its railroad depot, Atlas was a coal patch town populated mostly by Italian immigrants like those on my mom’s side (Dallago’s) and dad’s side (Greco’s – see my blogpost about Papap Greco here).

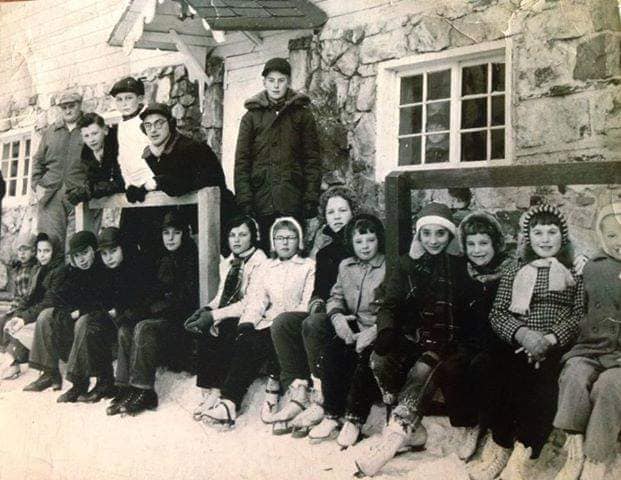

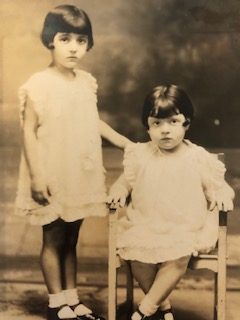

Rosemary (left) and Annabelle (right) Dallago

Annabelle (left) and Rosemary (right) Dallago

Nana once told me that in elementary she and her sister Rosemary were called “Greenies” by their own teachers, a reference to immigration Green Cards. Teachers also grabbed them by the ears and made fun of their earrings; at that time it was customary for Italian mothers to pierce their little girls’ ears at the time.

The Dallago sisters, though best of friends, could also fight like the fierce sibling enemies. The close bond between the two firecrackers would last a lifetime. Nana had bright red hair, which she was proud of her whole life. She and her sister worked in the local cigar factory, which, along with garment factories, was a major employer of women in the area. The men worked in the mines.

Yearbook picture of Annabelle Costello

Formal Picture of Annabelle Costello

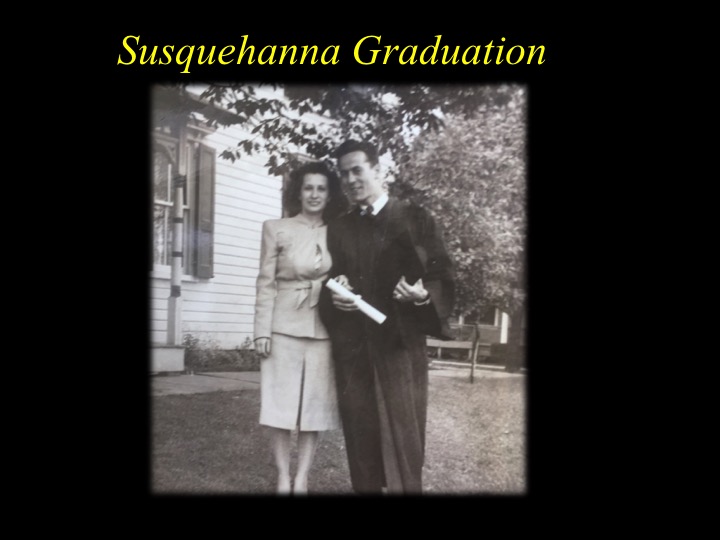

Nana married my grandfather, Joe Costello, when they both were 17. (See my blog post on Papap Costello here). The two eloped to Maryland because Papap Costello’s Irish mom didn’t approve of him marrying an Italian girl. Soon after they married he enlisted in the Navy and was shipped over to the Pacific theater to fight in WW2. I once asked my grandmother why she decided to marry Papap Costello. She shot back “we just got married. That’s what you did in those days.”

RAISING A FAMILY

After Papap Costello returned from WWII, he and Nana bought a house on Saylor Street in Atlas where they raised their three children: my mom, and her two younger brothers Joseph and Larry. My great grandmother, “Granny Dellago”, also lived with them, helped raise the kids, and ran the kitchen featuring her homemade Italian cooking. My mom was very close to Granny Dellago, and because the house was full, they shared a bedroom until the day my mom was married.

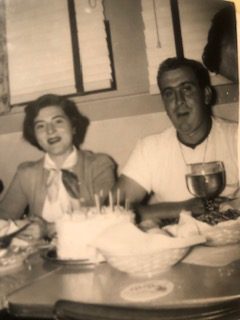

Joseph and Annabelle Costello

Joseph and Annabelle Costello doing their best “Bonnie and Clyde”

The Saylor Street home, like most homes in the Coal Region, was initially a 12 ½ ft wide “half-a –double”. Eventually they bought the other half-a-double, and knocked down interior walls. My mom remembers my Papap Costello working on the renovations for several years, pounding in every nail himself. For a long time the house always felt under construction, room by room. Eventually there was a cozy living room and nice dining room on one side, and a homey kitchen and family room on the other. The dining room was the site of the famous confrontation between Italian syndicate enforcer Felix “Screendoorface” Mangialetto and a dishwasher salesman who tried to talk Granny Dellago out of her money.

Papa and Nana Costello with daughter Candace (my mom)

Costello’s with daughter Candace

Papap and Nana Costello with my Mom and my Uncle Joe

I knew this house well, spending countless hours there while growing up. It had a huge grassy yard, the spot of an empty double lot, with a picket fence wrapping around the corner. A signature pear tree sat smack in the middle and bore fruit every year. Across the alley and up a steep incline there was a playground and even little league field, where I once hit a game winning home run over the fence towards Nana’s backyard.

Nana took great pride in this house. I’ll never forget the first time my other grandparents got to see it, when picking me up at Nana’s one winter evening. Doc and Eleanor Greco themselves owned one of the nicest houses in nearby Mt. Carmel, a huge, four story corner home on Hickory Street with a basement “rumpus room” created by the famous designer Ruben Bogenhorn. When they came to the back door, Nana Costello insisted Nana and Papap Greco come inside to see her warm, well-kept with abode with antique furniture passed along from Granny Dallago. I remember there was an electric space-heater turned on that night, and we had been watching TV under a few of the many afghans Nana had knitted herself. “Don’t you like my house, its very cozy”? It was important to her that Doc and Eleanor Greco see that she had nice home too.

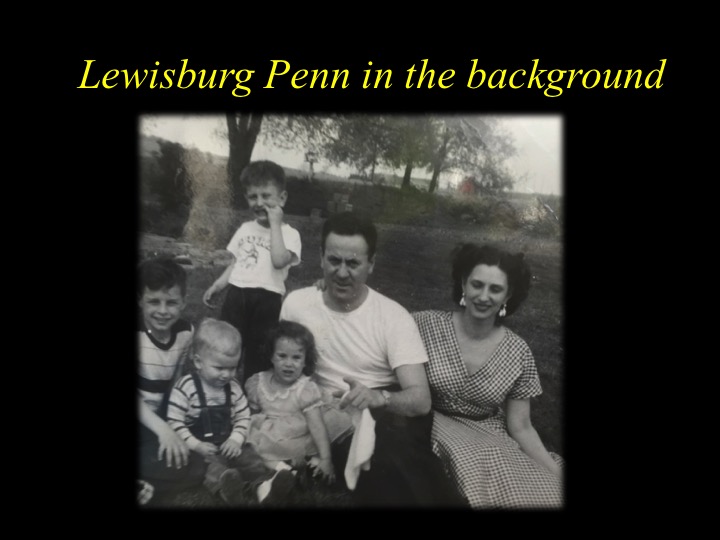

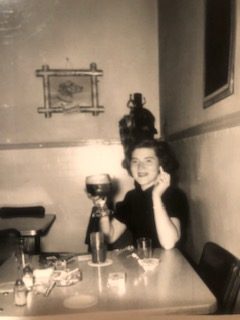

While raising their family on Saylor Street, Nana worked at the Selinsgrove State Hospital and Papap Costello worked in the mines, first underground, and then eventually working heavy machinery above-ground. They also owned a bar across the street for a while, and with the help of Granny Dellago, ran a pizza delivery business out of their kitchen. Granny Dellagos’ homemade Italian food was famous in the neighborhood, and my mom remembers her always having enough pasta, bean soup, or homemade bread for any local kids who hadn’t eaten that day. Nana managed the finances of the house, and as my mom said “somehow made it work”, even when the family had debt.

These were my Papap Costello’s prime years as civic leader when he was a Grand Knight in the Knights of Columbus, member of the American Legion and the Atlas Fire Company, and was elected to the Mt. Carmel Area School Board.

This time was also marked by Papap Costello’s battle with Rheumatoid Arthritis, which onset in his early 30’s during a time where there was very little effective treatment. His arthritis led to a series of related illness and the spiraling of his health until he passed away at age 43, when my mom was pregnant with me. She remembers Papap crying when she brought my older brother Gary, his first grandchild, to visit him in the hospital.

Having a husband stricken with a debilitating disease at such an early age must have been incredibly painful for Nana and the whole family. My mom was a young teenager when he first got sick, and she said that her childhood ended at that point and she was thrust into adulthood, having to help take care of the family. Up until the time my mom was married, she handed over her paycheck to Nana. Granny Dellago did the same with her monthly $66 Social Security check, which she endorsed with an “X” on the back.

Nana was widowed with three children at age 43 in 1970. My mom was married with two kids. My Uncle Joe, a high school football standout, was playing football in college. And though my Uncle Larry was still in high school, Papap’s death ushered in the next, more independent phase of Nana’s life.

INDEPENDENCE

For the rest her life Nana would receive a “Black Lung” check, the U.S. Department of Labor’s compensation to miners and their dependents from the debilitating effects of pneumoconiosis, which Papap Costello developed after years of working in the mines. This payment alone couldn’t support her, but provided a base income from which to build from. After a period of mourning, Nana secured work with the Mt. Carmel School District, and by the mid-70’s became the Library Assistant in the Jr./Sr. High School library. From this position Nana would begin flourish, vastly broadening her social network and investing in her intellectual growth.

While before this point Nana’s life centered around family, her neighborhood, and related civic organizations, but now she had access to a wide range of professional and social relationships with teachers and staff members at the school, which in a coal mining town with a dying economy, increasingly became the center of the community. She made the most of the opportunity, developing relationships with a lively bunch of colleagues who gave her a new nickname: “Bellsy”. She could be both one of the girls and one of the guys. Nana was still working in the library when I entered 7th grade, and well after she retired teachers spoke fondly of her.

But working in the library provided her with something else though: access to a wealth of literature. Though she had been a casual reader before, Nana became a voracious one now, systematically devouring everything in the library. A self-taught student of history, politics, religion, as well as some fiction, she especially loved reading about pivotal 20th Century political figures and historical moments of great gravity. Her own weighty temperament and sense of purpose led her to these subjects. As a 7th grade student I can remember seeing her read in a room off of the main library during her break.

Nana’s reading appetite continued well after retirement when she became one of the most prolific clients of the Mt. Carmel Public Library, again checking out everything she could get her hands on. Scattered about her house would be a book on Kissinger atop of an end table, a biography of John Paul II on the coffee table, and history of the Great Depression next to her morning coffee in the kitchen. “I make a GOOD pot of coffee,” she would sometimes brag.

Nana debated politics rabidly, and was the definition of a Pennsylvania conservative Democrat. She loved Chris Mathews, whom she called “Chrissy”, and cable news was always on in her house. Nana always stood with the “little guy” economically, but a daughter of the Church socially. Nana used to say that for generations our economy had been “rigged against the little guy”, and that despite the American Dream, it was nearly impossible for the poor to become rich.

When it came to Presidential elections, Nana supported whom she felt was best for the job, regardless of party. She voted for George W Bush in 2004, mostly due to a letter on abortion that Pope Benedict issued. But in 2008, after I showed her another letter Benedict wrote giving Catholics some flexibility despite a candidates position on abortion, she voted for Obama.

Nana always felt an affinity for Jewish people, so much that she believed she might have Jewish blood. She kept a Mezuzah in her doorway, just above a small holy water cistern. I once brought a friend home from college, who happened to be Jewish. My grandmother loved her. Years later my friend, Amy Sohn, made a name for herself by publishing a weekly racy dating column in the New York Daily News: sort of a “Sex in the City” but a few notches more risqué. On a visit home to Mt. Carmel several months later I saw a stack of Daily News editions on a magazine rack table. It turned out her neighbor was a subscriber, and gave Nana his copy every week, which she read with fervor.

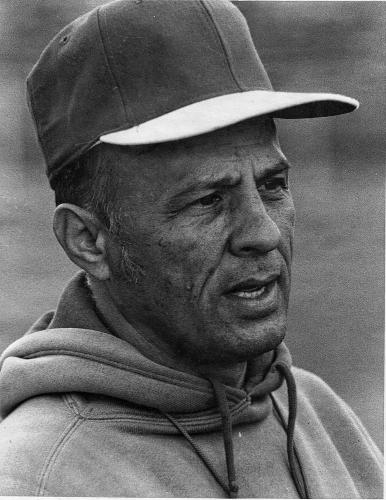

Starting in the early 1980’s Nana began to spend time with a companion named Leonard. Leonard was always nice to us: he took us fishing, wrestled with us, told us jokes and old stories of his time as an undergrad at during the heyday of college football in the 1950’s. At one point he and Nana moved to Levittown, PA where he worked in a steel mill.

Every summer we also trekked to New Brunswick, New Jersey, where my Aunt Rosemary and her family had moved several years earlier. It was fun to get out of the small town for a week and spend time with family in a city environment. After mining was in decline, lots of young men from the Coal Region would look for industrial work outside Philly and in New Jersey. Some travelled back and forth every week and some moved for good. My Aunt Rosemary and Uncle Vic moved to New Brunswick, Leonard to Levittown, and my mom says her own family had moved to New Jersey for a year when she was a young girl to be closer to Papap’s Costello’s job at the time. Not wanting to move, my mom stayed behind with relatives, and after a year her family returned. I’m glad they did, because I wouldn’t trade growing up in a town like Mt. Carmel.

During this part of Nana’s life my mom was raising 3 kids and sometimes felt Nana wasn’t as available to help as my mom would have liked. Granted, my mom shared my Granny Dellago’s nurturing instinct, while Nana was a bit tougher around the edges. And having raised 3 kids of her own, and needing to build her independence in a way Granny Dellago never had to, Nana channeled a bit of Mary Tyler Moore. But I always felt her a strong and constant presence in my life.

(Below are Pictures of Nana with my family, including my parents at center, and at the New Jersey shore with my mom, my older brother Gary, myself, and younger brother Joey)

On the other hand, there was the story of Spunky. We kept Spunky, a lively white hamster, in a cage replete with exercise wheel and colored tubes, next our television for about a year when I was 10 years old. While babysitting one night Nana slept on the couch, as she normally did after we went to sleep. We woke up the next morning to find Spunky gone: he evidently bent the wire top to the cage in one corner and escaped. Nana and my mom helped us look for Spunky all day to no avail. We looked for him every morning for a week, but eventually accepted he escaped for good.

But years later, while reminiscing with Nana about growing up on Hickory Street, the conversation turned to Spunky’s great escape. Nana started laughing and asked “didn’t I ever tell you what I did?”. Evidently, that fateful night, Spunky wouldn’t stop spinning in his wheel and kept Nana awake for hours. Not one to tolerate extravagancies such as nighttime exercise, Nana got so frustrated that she tore through the wire cage top, grabbed the rodent, opened the cellar door, and jettisoned Spunky down a deep flight of stairs towards the cold cement floor. Unless he had learned to fly, it seems Spunky met something short of a positive outcome.

MATRIARCH YEARS

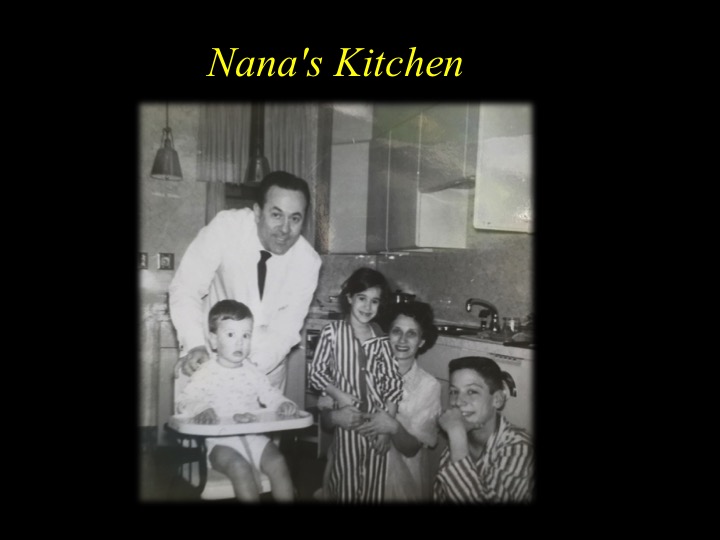

The matriarch phase of Nana Costello’s life started after she had moved back to Mt. Carmel from Levittown and eventually bought a house on 3rd street. It was a well-kept, half-a-double with beautiful wood molding and a wooden archway separating the family room from the living room. The kitchen also had well-finished light wood cabinetry. There were two nerve centers in the house: the first was the living room TV which was built into the wall under the staircase. It always played cable news. And the second was the kitchen table, where Nana ruled the roost.

Think of the kitchen of Nana’s “Situation Room”, where a president or head of state would receive information, debate strategy, and issue commands. Nana chaired all conversations from the head of the table, a can of Coke placed on a napkin to her right, a pad and pen to jot down notes, and a pack of cigarettes before she quit smoking.

On our visits home from college we visited Nana individually, where she would indulge us in long conversations ranging from family updates, to town gossip, and national politics. She gave each of us our own individual time and had a personal relationship with each of her grandchildren. This was also an opportunity for Nana to absorb information about the outside world, the places where we went to school and eventually lived: Washington DC, Providence RI, New York, Los Angeles, Austin, Philadelphia. This kitchen table was also the place where she sometimes sat alone to think, worry, and strategize about her family.

The ultimate family celebration each year would be Nana’s Christmas Eve dinner, executed with the precision of a Swiss Watchmaker. Born over years of practice at the Saylor Street house, under the tutelage of her Granny Dallago, Nana combined authentic Italian cooking skills with the discipline of a drill sergeant. Now in her 70’s, Nana’s feast normally fed 15-20 people, including 3 grown children, 7 grandchildren, spouses, significant others, and eventually great-grandchildren.

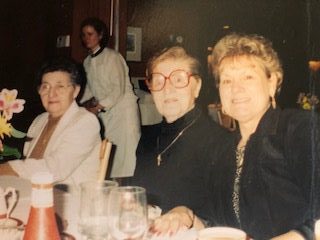

From left: My mom, Aunt Rosemary, Nana, My Aunt Jan and Uncle Joe Costello, and my Aunt Donna and Uncle Larry Costello

The family would gather Christmas eve around 4pm, place gifts under the tree, drink high-balls, and shoot the shit. There were a lot of comedians in the house so nobody went away unscathed. Nana was to be left alone cooking unless she asked for help lifting a pot or grabbing something from the basement.

At precisely 5:30pm she summoned us to the kitchen table. First was Italian Wedding Soup, a recipe passed down from Italy through my great-grandmother. A savory potion of chicken, meatballs, eggs, and signature “bubbles” or tiny dough dumplings. No sooner had you spooned up the last bit of delicious broth then your bowl was scooped away by Nana or one of her bodyguards, my Uncle Joe or Uncle Larry. It wasn’t that second-servings weren’t allowed: it’s just that the main course was on its way, and the forward trajectory of the meal didn’t allow for pauses in the action.

Then came the “home-maders”. These were handmade ravioli assembled weeks earlier at my Aunt Donna’s house, the home-made pasta shell was filled with the same small meatballs that were in the wedding soup. After topping it with Granny Dellago’s signature pasta sauce, you would spoon on liberal portions of “shaky cheese” as Nana called it. Shaky cheese was fresh grated parmesan, also sometimes called “Hazelton Cheese” if Nana procure it from a particular Italian deli in the nearby Pennsylvania city of the same name.

Rounding out the meal were breaded chicken cutlets, a nice salad, olives, and fresh made bread from Barkers Bakery or Hollywood Pizza. The meal was in constant motion, with dirty plates swept away to make way for clean ones. Seconds were welcomed but you needed to grab them fast or they would be snagged by the competition. The meal was served and devoured in less than 45 minutes, and if you left the table hungry it was your own fault. Genuine Italian cooking at American-pace eating. Fast, efficient, and delicious.

After dinner we retired to the living room to exchange gifts, a logistical ordeal involving three generations, several nuclear families, etc. After most of the gifts were torn open, the main event arrived. Everyone paid tribute to Nana with their presents, and with each one Nana bellowed her trademark “Ohhh…..Ohhh my God!” a dramatic representation of her appreciation, delivered with exactly the same exuberance each time, not wanting to favor anyone.

“Ohhh!”

“Ohhhhhhh!”

Then came the envelopes. Sitting on a rocking chair seldom used but for this occasion, Nana doled out her largess to the family in the form of a packet of Christmas money-envelopes, bound in a rubber band like the Academy Awards. Each bore the name of one of her minions, with exactly the same cash amount in it. The only variety was the occasional raise we got. But all employees, no matter their station or degree, got the same amount. Nana played no favorites.

The biggest loss of Nana Costello’s life was the early passing of her grandson, Joey Costello. Joey was the younger son of my Uncle Joe and Aunt Jan Costello, and was several years younger than me. Joey had won two State Football Championships, was named All-State two years in a row, and held the career record for tackles at Mt. Carmel, the winningest team in Pennsylvania High School history. Joey represented the heart and soul of our family. He was a leader and tireless worker on the field, and also had a big personality that lit up the room off the field.

Joey died in a construction accident in 2004. He left behind a widow and young son. His passing devastated the entire family, and in a very deep way, Nana Costello, who grappled with it for a long time. Though she had lost her own husband at 43, nothing prepared her for this. As we sat at her kitchen table months after Joey’s passing, Nana used a metaphor to help her understand her loss: “God never gave me any real diamonds. My only diamonds were my seven grandchildren. I guess God felt I had too many diamonds, so he took one back from me.”

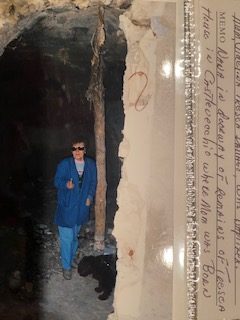

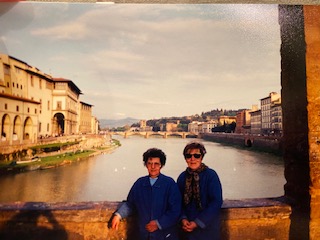

One of the biggest joys in my grandmother’s life was her trip to Italy in their early 70’s with her sister and my younger brother Joey. Granny Dellago was from Castelvecchio, a small town in the impoverished Abruzzo region of Central Italy. This was their first and only trip to Italy, and they paid Joey’s way to be tour guide and translator (he had learned Italian in college). The origins of the trip started a year earlier, though, when my brother Joey and cousin Jeff Greco went backpacking across Europe.

The sisters at Ponte Vecchio

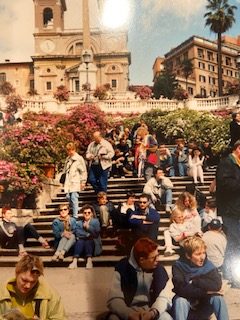

….on the Spanish Steps

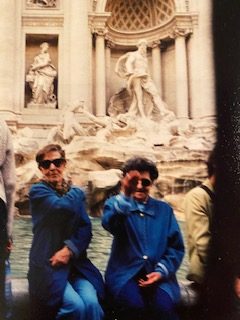

and at the Trevi Foundtain

According to Joey, “I originally found the town while backpacking with Jeff the year before taking Nana and Aunt Rosemary. We took a random train in the direction of Castelvecchio and the conductor found us a fellow passenger to drive us there from the nearest stop.”

When they arrived in the small town nestled in the Central Appennine mountains, they made their way to the medieval stone piazza which seemed asleep except for a few restaurants and bars. Newer houses surrounded old part of the city. Armed only with the name Lena (Granny) Dellago, and her maiden name, Tresca, they entered a bar filled just with the owner-bartender and a few patrons.

“We told them our story.” Joey recounts. “He then shut down the bar and walked us to the town hall while along the way other townspeople joined us as he told them he had a couple Americans looking for info on the Dellagos. At the townhall they found the birth certificates of Granny, her parents and brothers. At that point the bartender jumped to the phone to call Leno (Tresca) once he put two and two together.”

Leno flew down in his car and swooped Joey and Jeff back to his ranch style home where they spent the night. They called Nana Costello in Mt. Carmel later that night to let her know they found her relatives. She broke down in tears.

After Joey returned home, Nana and Aunt Rosemary resolved to make the pilgrimage themselves to Castelvecchio if they could manage it financially. Fortune struck when my Aunt Rosemary, and avid Atlantic City gambler, hit at $10,000 jackpot at a slot machines. This “dirty money” funded the trip to the Italian homeland for the two sisters, with Joey as their chaperone, the following year.

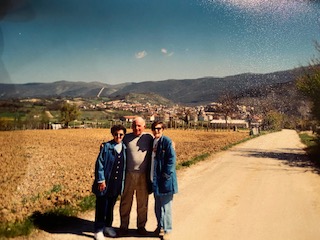

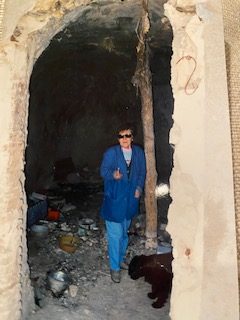

Once they made it to Castelvecchio, cousin Leno and his family met the three at the train station and drove them back to his house where they spent a few nights. They ate, drank, told stories with their cousin Leno and the whole family, including their own “Nona”, a thin and wrinkled women in her 80’s who just rocked in her chair, listened, and said nothing but “Mangia”. During the stay they also visited the run-down stone home that Granny Dallago was born in and raised until she travelled to the U.S. with her father at age 14.

(Nana, Aunt Rosemary, and Joey meet our relatives the Trescas in Castelvecchio below)

The culmination of their trip to Italy was a visit to the Vatican, where they hoped for a glimpse of the Pope waiving from his balcony where he often emerged on Sunday afternoons. They arrived in the morning, so to pass the time they endeavored to gain entrance to a service in St. Peter’s Basilica. There were long lines, but my brother pulled the two the pilgrim sisters towards the front of the crowd. The security man must have sensed Nana and Aunt Rosemary were devout Catholics with their Rosaries in hand, and he pulled them and Joey into the entrance like a New York nightclub bouncer would pull a couple of sexy young women out of a long line and into the club ahead of others.

Seated in chairs near the back of the church they began speaking with a nearby group of nuns from America. After telling the nuns of their desire to catch a glimpse of the pontiff at his balcony later, the nuns, stunned, asked “Don’t you realize the Pope will be saying this Mass? We had to apply for tickets to this over a year ago!”

They were stunned, and were mesmerized the entire service, including his final procession down the center aisle to bless worshipers. When he neared the back, Nana and Aunt Rosemary bullied their way to the aisle and climbed on top of two chairs. They caught a divine break when JPII stopped right in front of them and gave a blessing directly at them with the sign of the cross. Aunt Rosemary, who had been battling cancer for the past few years, later claimed that all the pain in her body vanished at that moment. It seemed all those years of attending Masses and saying Rosaries paid off for the sisters from Atlas.

You might sense a contradiction in Nana’s distain for the Robber Barons who built The Breakers and the other Newport mansions on one hand, and her utter adoration of the Pope and rich Vatican splendors like the ornate St. Peter’s Cathedral. Even during the toughest economic times, Nana gave religiously to collection plates at Mass. And she always made sure we as kids had a few dollars to give in the pews: “I have ones! I have ones!” she said as she gave us the bills. The difference to a working class Catholic like Nana was that she believed the Church belonged her and the other parishioners. This included Vatican City which had a special relish because it was located in our family’s homeland. As one of my favorite theologians, Stanley Hauerwas, once said about Cathedrals: “Poor people deserve to own something beautiful too”.

EPILOGUE

My cousin Jeff Costello recently comment that given Nana’s intellect, moral compass, and personality, she would have achieved great things professionally in business, politics, or another profession had she been able to college rather or lived in an area with more opportunity. This echoed the message in the eulogy my brother Gary gave at her funeral a decade ago. While no one in our family doubts this, there actually is an interesting “test case” which lends strong support to Jeff’s statement: our Aunt Rosemary.

Rosemary Sufalko, Nana’s elder sister and best friend, moved to New Brunswick New Jersey after getting married. To help support her family she cleaned offices, including one which housed a market research firm. Austin Rosemary once told me that, because of her dependability, the office manager asked her if she would do doing some clerical work in addition to her cleaning. Not wanting to spend more time away from her family, she agreed only if she could bring the work home with her. She excelled and was rewarded with a full-time secretarial job. It became clear over time that her talent and hard work warranted more opportunities and promotions, and Aunt Rosemary eventually became an executive at that firm, working directly with TV networks and media companies.

Given the opportunity, I have no doubt Nana would have reached similar heights. Her field would have been politics though. She could have been a mayor, a school board member as her husband had been, or even a legislator. Nevertheless, she always built strong relationships locally with those with power and influence.

Her close relationship with my paternal grandfather, also a school board member, gave her an ear to bend on important decisions in the district. Throughout her career she also had a close friendship with the school district Superintendent, whom she knew from Atlas. He was a Lou Grant type, for whom she often acted as a sounding board, unofficial advisor, and advocate on behalf staff members, where she had deep relationships and credibility.

Nana told me stories, the specific details of which I’m sworn to secrecy, about lobbying Papap Greco at his kitchen table for hours, or calling the superintendent at home to do the same. Once when trying to reach the superintendent by phone, his wife answered and said he was taking a shower and therefore unavailable. Nonetheless Nana demanded he take her call. Minutes later he was standing, dripping wet on the other end of the line, all ears, as Nana pressed him on one issue or another.

Nana has had a huge impact, politically and otherwise, through her children, grandchildren, and everyone else she touched. She exerted a dominant moral influences in all of our lives, and we can hear her clear voice advising us when facing the toughest decisions about family, work, or life in general. The line she delivered at The Breakers sticks with me to this day.

She was my mom’s best friend, and their relationship deepened after my parents’ divorce, and was marked by a mutual dependence on each other. During Nana’s last days, when it was clear she would pass, my mom put her on the phone so we could talk with her one last time. She was still aware and attempted to speak, even though she went in and out of consciousness. And according to my mom, Nana’s last words were “There’s Crissy”, as she pointed to the hospital TV playing the Chris Mathews show.

Nana passed away in an ambulance, with my mom by her side, as it took her home where she wanted to spend her final days. A few years ago, at a time when my mom was especially missing Nana, my brother Joe and his wife Vicky named their first daughter Annabelle, as a tribute to the matriarch who set a high standard for us all. But through her life and her love, she gave us the ability to meet it.

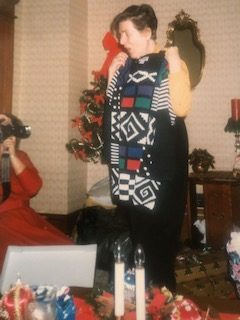

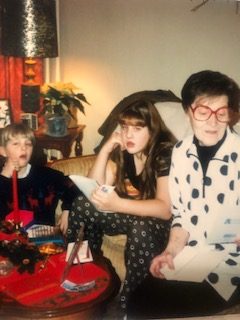

Nana with her three children on Christmas Eve: Larry (left), my mom (right-center) and Joseph (right)

IF YOU HAVE ANY PICTURES OF NANA YOU WOULD LIKE TO ADD TO THE GALLERY, PLEASE SEND THEM TO ME